You gotta hear it again today

The way to crush the bourgeoisie is to grind them between

the millstones of inflation and taxation. ~ Vladimir Lenin

The certified nation-builder, Vladimir

Lenin, mentions above that inflation can be the bane of many people, even the

bourgeoisie. He’s right. Milton Friedman, a certified Nobel-laureate economist,

but not at all a fan of Lenin, stated that inflation is taxation without

legislation. He’s right, too. They agreed about nothing political, but do agree

about the harsh effects of inflation that reduce the purchasing power of money.

Inflation is a general rise in a

nation’s prices. Not just the increasing price of fruit loops, Airbnb rentals

or window panes, but all prices in a country. Economists cite woeful, recent

examples of unchecked hyperinflation such as Venezuela’s 27,364% inflation in

2018, when prices doubled about every two weeks and Zimbabwe’s 66,000+%

inflation in 2009. The “winner” in my national hyperinflation hall of fame is

Hungary’s unfathomable 1946 general price increase of 9.63 x 1026 percent

(prices doubled in less than every one and a half days). Post-war periods and

inflation often coincide. Even here in the good ol’ USofA. Cliometricians

estimate that in 1779 the US had an inflation rate of 192%, mostly caused by

the Revolutionary War’s substantial costs.

Have you experienced noticeable

national inflation? Not unless you’re over 35 years old with virtuous long-term

memory. The last time the US core Personal Consumption Expenditure price index

(PCE), that our Federal Reserve Bank uses to measure official price

changes, reached 5% annual inflation was the third quarter of 1983. The

PCE has only been over 2% – the Fed’s target inflation rate – in merely two (2)

of the most recent 40 quarters (10 years). Long gone are those economically-stormy,

early 1975 days when inflation rose to 10.1%.

Thus, with perceptible inflation

thankfully being in a long-term coma it’s hardly surprising that last week

Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell and his colleagues altered the Fed’s policy

priorities. Going forward, the Fed will re-emphasize its goal of minimizing

unemployment rather than its second goal, controlling macro prices (e.g.,

inflation). The Fed stated that low unemployment would no longer be a

sufficient reason to tighten monetary policy, in an attempt to head off

expected inflationary trends. In a remarkably truthful statement, the Fed’s wizard

vice-chair, Richard Clarida, stepped in front of the curtain to state that the

Fed’s macroeconomic models that have predicted inflation would always rise

significantly when maximum employment was reached were wrong.

Apparently, Senate leader Mitch

McConnell didn’t get this Fed memo, as he’s staunchly refusing to re-vitalize

expansionary fiscal expenditures – such as the former $600 unemployment

supplement – to ease the lives of too many people, and reduce unemployment. Mitch

dismisses the facts that unemployment is now 10.2% and folks are suffering.

For a long time, both the Fed’s

goals were nominally given equal policy priority. This dual prioritization was essentially

founded on the Phillips Curve. In case you’ve forgotten this slight theme

presented in Econ 101, here’s a recap.

The Phillips Curve is named after

Professor William Phillips, my favorite New Zealand economist. He gained my fancy

in part because he’s the only economist I know of who was a crocodile-hunter in

his youth. After fighting in Southern Asia during WWII, he headed for London

and enrolled in the London School of Economics (LSE). At the LSE he became captivated

by the then quite radical, newish view of macroeconomics created by John M.

Keynes and became an academic economist.

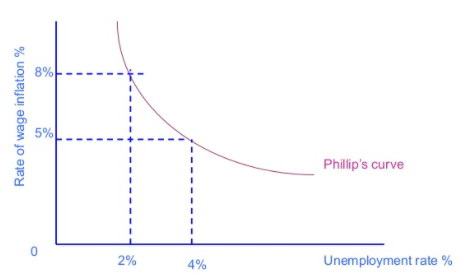

In 1958 Professor Phillips

published his seminal paper that described an inverse/indirect relationship

between a nation's wage-inflation rate and the unemployment rate using early-20th

century United Kingdom data. When either unemployment or inflation is low, the

other is high, as illustrated below.

The Phillips

Curve

Source:

Forex

When similar patterns of wage-inflation

and unemployment were observed in other nations at the time, the Phillips Curve

became accepted by both academics and policy-makers. If an economy was growing

with lower unemployment (higher employment), the Phillips Curve posited that higher

wages/inflation will happen. It displayed the short-run macroeconomic trade-off

between a strong economy (lower unemployment) and higher inflation.

This relationship has not held in

more recent times despite considerable efforts to defend the Philips Curve and

its shape. Some macroeconomists have differentiated short-term versus long-term

Phillips Curves, others have added inflationary expectations to no real avail. I’ve

believed the Phillips Curve has been a chimera for quite some time. But the

Congress and the Fed, as well as other nations’ legislatures and central banks,

still use the explicit Phillips Curve’s inflation-unemployment relationship for

justifying policy.

When inflation appears set to

rise, the Fed has typically tightened the money supply (by increasing interest

rates), generating a little more unemployment. When inflation is poised to

fall, the Fed has done the opposite. The result is that unemployment edges up

before inflation can, and goes down before inflation falls. Monetary policy

(and to a much lesser extent fiscal policy) is changed so that inflation will

not.

But inflation has appeared to be

less sensitive to differing employment levels, as mentioned above. Inflationary

pressures have been in a coma. This past February (a lifetime ago) when the macroeconomy

was quite strong with very low 3.5% unemployment, the PCE inflation rate

was a remarkably quiet 2.1%.

The Philips Curve has apparently

flattened over the past decade, so that a given change in unemployment, due to

variations in monetary and/or fiscal policy, has had a smaller effect on wages/inflation

than previously. This change is the basis for the Fed’s recent prioritization

of fighting unemployment with much less concern about eventual inflation.

Oh my, Professor Phillips, your curve

has broken down and metamorphosed over time to be far flatter, in spite of some

macroeconomists’ best efforts to explain this change and do something about it.

The Fed is going to focus now principally on promoting employment, downplaying

price-stability.

That’s perfect timing because we’ve

been in a significant recession for at least five (5) months. The Fed’s Board

of Governors now will “appreciate the benefits of a strong labor market,

particularly for many in low- and moderate-income communities.” After this Spring,

when the Fed began its sizeable efforts to reduce the pandemic’s recession, will

inflation awaken from its long, Ambien-induced torpor? A pro pos of the

well-known Niels Bohr quote, predicting inflation is very difficult, especially

about the future. But it appears that most economists and market analysts,

despite voluminous and contrary opinions, do not think noteworthy inflation is

anywhere near imminent.

I think the recent flatness of the

Phillips Curve has contributed to the rise and spread of progressively-liberal

economists’ Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). A simplified tenant of MMT argues

that countries which issue their own currencies, like the US does, can never

“run out of money.” The federal government is not financially constrained in

its ability to spend. MMT claims that the government can afford to buy anything

that is for sale in its currency with minimal concerns of resultant inflation.

Ironically, when Dems come into

full federal power on January 20, 2021 with enough of them subscribing to the

flatter Phillips Curve and MMT, they could embrace the Repubs own de facto

fiscal policy that has exploded the federal budget deficit with their specific,

pet fiscal initiatives like giant tax cuts for corporations and for the bluest

of the rich as well as ever-increasing defense expenditures, with no

discernible rise in inflation.

By brandishing the Phillips Curve’s

modern flatness, adopting MMT and pointing a fiscal mirror at #45’s and

the Repubs’ massive deficit spending, progressive Dems could justify, with

enough backbone, their own expensive, pet fiscal initiatives. Ones like the Green

New Deal, government-guaranteed $15/hr jobs and Medicare for All. It could be

the Dems’ way of stating, if you Repubs can do and have done it, we can too for

far broader benefit.

In my mind, it all started with

one clever, crocodile-hunting Kiwi economist.

No comments:

Post a Comment